Architects and developers have been encouraged to build green for decades, resulting in the use of sustainable building materials, greater energy efficiency and more generous allocations of open space. But a dramatic movement has emerged in which agriculture is literally integrated into architecture and the approach, known as “agritecture” or biophilic design, represents the current frontiers of sustainability.

Many buildings, usually incentivized by government agencies, earn certifications for sustainable design, but others are literally green. The agritecture trend began manifesting itself with rooftop lawns, athletic fields or gardens, which not only injected precious green space into densely populated cities but also reduced energy costs. Living walls began popping up in trendy restaurants and hotel lobbies, but these gestures hardly captured the true potential of the movement.

The terms agritecture or biophilia were hardly in vogue, even imagined, during the career of Frank Lloyd Wright, but some experts view him as one of the most influential early proponents of the theory. Wright’s most iconic home, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, is perhaps the ultimate example of an architect incorporating nature into the built environment, a consistent doctrine of the legendary designer.

Literally built over a cascading waterfall, Fallingwater complements rather than overwhelms the extraordinary site, and Wright deserves some credit for innovations occurring half a century after his passing. Many contemporary architects, even those who may dismiss Wright as too mainstream to be cool, emulate his commitments to sustainability and blurring boundaries between indoors and out.

Frequently cited as the poster child of the agritecture movement is Bosco Verticale (“Vertical Forest”), a residential complex in Milan, Italy completed in 2014. Conceived by the pioneering eco-conscious firm of Stefano Boeri Architetti, the development features large, mature trees seemingly sprouting from the terraces of its two towers. Like most biophilic projects, the inspiration was to reduce greenhouse gases while introducing inviting natural elements into an urban setting. Founding partner Stefano Boeri collaborates with designers to re-create his Vertical Forest concept around the world.

“The design allows an excellent view of the tree-lined façades, enhancing the sensorial experience of the greenery and integrating the plant landscape with the architectural dimension,” says Boeri.

The firm’s first Vertical Forest project in China, a five-tower residential complex in Huanggang, features more than 400 trees, 4,600 shrubs and 26,000 square feet of grass, flowers and climbing vines. “The design allows an excellent view of the tree-lined façades, enhancing the sensorial experience of the greenery and integrating the plant landscape with the architectural dimension,” says Boeri. “Thus, the inhabitants of the residential towers have the opportunity to experience the urban space from a different perspective while fully enjoying the comfort of being surrounded by nature,” adds the architect.

In Eindhoven, Netherlands, the Vertical Forest concept was applied to affordable housing in a 19-story tower comprised of 125 modest apartments. Insisting that an eco-friendly living environment should not be reserved for the affluent, Boeri states, “Living in contact with trees and greenery, and enjoying their advantages, could well become a possible choice for millions of citizens around the world.”

Courtney Crosson, assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s College of Architecture, Planning & Landscape Architecture, has practiced architecture around the world with celebrated firms like Foster + Partners. In her research and teaching in Tucson, her interpretation of agritecture focuses on agricultural activity in central cities, which yields multiple benefits.

“Urban agriculture reconnects people with their food sources, lowers the carbon footprint of food production and educates consumers about the seasonal characteristics of agriculture,” explains Crosson. She cites Brooklyn Grange in New York, the world’s largest rooftop farming operation, as representing a positive example of the intersection of urban agriculture and urban planning.

Crosson reports that most architecture school curricula address biophilia — relating to human beings’ affinity to nature in their everyday lives — to varying degrees. “Studies have indicated positive outcomes from having more natural materials in the workplace, home or hospital,” explains Crosson, who notes such influences can be as modest as a living green wall or even the use of fabric patterns inspired by flora.

The professor is more skeptical of the flurry of skyscraper proposals featuring cantilevered terraces overflowing with mature landscaping, whose execution can be challenging. Conceding the appeal of those renderings, Crosson states, “They look utopic for a reason, and I think this new way to envision urban dwelling is hopeful.”

She reports people respond favorably to the presence of natural elements in their neighborhoods, citing the success of the High Line in Manhattan, a swath of parkland created from an abandoned railroad spur designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Many Americans are surprised to learn that Singapore, with its reputation as a congested, antiseptic glass-and-concrete environment, is at the forefront of the biophilic revolution. Despite its high population density, the city-state is living up to its vision as a “garden city” and the prominent local architectural firm WOHA is furthering the transformation of Singapore into a green oasis.

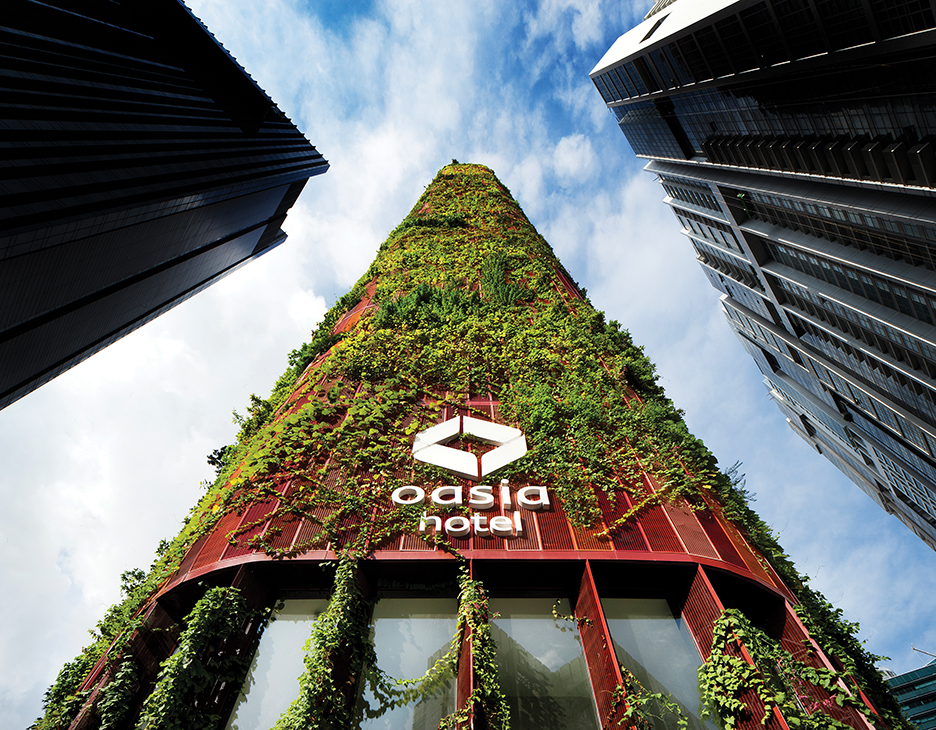

Presented in the firm’s book Garden City Mega City: Rethinking Cities for the Age of Global Warming, WOHA’s projects integrate natural elements with bold aesthetics. Singapore projects such as Parkroyal Collection Pickering (a hospitality/commercial center) and Oasia Hotel Downtown feature explosions of greenery that soften the contemporary architecture and reduce greenhouse gases while enhancing the quality of life of occupants.

Articulating the inspiration for the Oasia Hotel, WOHA founding director Mun Summ Wong explains, “We’ve almost created the notion of a huge tree in the city, where animals could thrive in the canopy.” He adds, “We wanted to reintroduce greenery back into the cityscape, to envision a new skyscraper for the time.” Since the Oasia Hotel’s completion in 2016, WOHA has conceptualized increasingly ambitious projects supporting the concept of a flourishing, three-dimensional ecosystem in the heart of the city.

In addition to WOHA’s green imprint on Singapore, outside firms are contributing to the city’s impressive collection of biophilic structures. Currently under construction is the 21-story Park Nova tower, a luxury residential project from London-based PLP Architecture that is a particularly graceful example of the genre.

In Melbourne, MAD Architects — some of the world’s most innovative and audacious projects are conceived by this Beijing- headquartered firm — submitted the “Urban Tree” for a design competition for Australia’s tallest building. Had it been selected, the skyscraper would have been a model of agritecture, with its soaring frame punctuated by greenery to soften the environmental and visual impact of the development. A more intimate biophilic project from MAD is Gardenhouse, a luxury condominium project in Beverly Hills whose façade is clad in a living mosaic of greenery.

The design competition for the Melbourne megaproject was ultimately won by UNStudio, a Dutch firm in collaboration with Australia-based Cox Architecture. Their concept, a pair of gently twisting towers dubbed the “Green Spine,” presents a vertical green landscape, while a public park on the podium level integrates more traditional open space into the $2 billion development. When completed in 2027, the project’s planting will absorb noise and air pollution while cooling the atmosphere on summer days. Building and landscaping materials will be native to Australia, reinforcing the complex’s theme of sustainability.

Amazon’s much-hyped HQ2 complex in Arlington, Virginia, slated for completion in 2025, is one of the nation’s highest-profile agritectural efforts. The centerpiece of the $2.5 billion project will be a 350-foot steel-and-glass tower with mature trees spiraling up the building, a design by Seattle-based NBBJ that was inspired by strands of DNA.

The “Helix” will not house cubicles and conference rooms but, like the biophilic “Spheres” at Amazon’s Seattle headquarters, will consist of recreational and collaborative spaces for employees and the public. The design of the HQ2 complex also features an immersive “Forest Plaza” offering a botanical garden-like ambiance for meditation, gathering with colleagues or contemplating Amazon’s next corporate acquisition.

Leave a Reply