Active lifestyles are driving consumer demand for walking and biking trails, causing developers and urban planners to rethink transportation.

By Camilla McLaughlin

Photo courtesy Visit Denver; ©Stevie Crecelius

What will shape cities of the future? Infrastructure, say experts at the Urban Land Institute (ULI).

ULI and a number of urban planners expect new modes of transportation such as shared cars and self-driving vehicles to change everything in cities, from the number of parking spaces to traffic. But these options are only a small part of transportation’s new paradigm, which takes into account multiple modes of navigation, especially in urban centers. Already a number of cities are committed to this vision, and are developing infrastructure to diversify transportation. Fourteen cities have heavy rail; 28 have light rail, which is growing fastest in the Southwest; and rapid bus transit is a reality in 36 cities.

Now planners and developers are also looking closely at bicycling and walking, which they consider active transportation. Not only are cities building trails and safer roadways for bikes, but a new generation of offices, mixed-use communities, and even resorts, incorporate biking and walking into the lifestyle they offer. And developers and homeowners are discovering these amenities have a big payoff. According to ULI, studies show that direct access to trail, bike-sharing systems, and bike lanes positively impact property values. As an example, they point to homes within a quarter mile of the Radnor Trail, part of Philadelphia’s Circuit regional trail network, where values on average were $69,000 higher than other area properties.

“Bicycling has recently undergone a renaissance in locations across the world, with an increasing number of people taking to the streets by bike,” observed the authors of a new report on active transportation published by ULI.

Worldwide, two-wheeled vehicles have traditionally been an accepted means of transportation, but usage has skyrocketed in recent years. Transport London found cycling in the city recently reached its highest rate since it began keeping a record. Bicycles outnumber cars on the road in Amsterdam, with the number of local trips increasing by more than 40 percent since the 1990s. In Copenhagen, the first two phases of a 311-mile network of cycle superhighways have been completed. Right now these two completed routes connecting the city with suburbs have between 3,500 and 4,000 users per weekday.

In the U.S., bicycling and walking were not historically considered part of the transportation continuum, but infrastructure improvements and the addition of bikeways and walking trails such as the High Line in New York or the BeltLine in Atlanta are boosting interest and moving walking and biking into the transportation conversation. “Cities that are investing in bike infrastructure are seeing big increases in bike use,” said Ed McMahon, coauthor of “Active Transportation and Real Estate, The Next Frontier,” speaking at a panel on trail-oriented development at ULI’s spring conference.

There is good reason that walkable has become real estate’s newest mantra. According to ULI, 50 percent of U.S. residents say walkability is a top priority or a high priority when considering where to live.

Build It and They Will Come

U.S. Census Bureau data shows that the number of people who traveled to work by bike increased by roughly 62 percent between 2000 and 2014. But ULI found that rates generally exceed the national average when cities invest in bicycle infrastructure, including new configurations for bike lanes, an increased number of protected bike lanes, and trail systems.

It’s no accident that Portland, Oregon, has the highest bicycle commuting rate among large U.S. cities — 7.2 percent compared to the less than 1 percent on the national average. That is a 400-percent hike since 1990. Transit in that period only increased by 18 percent, while driving declined 4 percent. The catalyst was a 300-mile network of bike trails, bike lanes and bike boulevards. The cost in 2008 was approximately $60 million, about the same as a single mile of a four-lane urban freeway.

Minneapolis, where 4.7 percent of the residents commute by bike (the second highest rate in the U.S.), has a long-term goal of having 15 percent of citywide transportation be by bike, and ULI’s experts say that’s not an unrealistic goal. Copenhagen and Amsterdam have bicycle commuting rates exceeding 40 percent.

Portland and Minneapolis may be setting the pace, but a number of other cities including San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Chicago report growing interest in biking, not just as a sport, but as a viable mode of urban transportation.

Banking on Biking

In recent years, the focus for planners has been transit-oriented development — mixed-use communities clustered around transit hubs. Some new communities are taking this a step further and adding active transportation, walking and biking, to their lifestyle focus. Hassalo on Eighth, a mixed-use project in Portland, Oregon, combines transit-oriented and trail-oriented development. Located near major bike routes and also with access to transit and light rail, it is the largest residential development in the city. With parking for 1,200 bikes, it also houses the largest bicycle parking facility in North America, open to both residents and area employees.

Bike amenities at Hassalo on Eighth are similar to those offered in a number of new communities across the country, and include on-site bike valet service, with bike tune-ups an option. Vending machines make parts for simple repairs readily available. And shower and locker room facilities will enable local bicyclists to change and shower after commuting.

In Atlanta, along the award-winning Atlanta BeltLine, a burgeoning 22-mile network of public parks, multiuse trails and transit facilities, new developments promoting a car-free lifestyle are springing up. Post recession, Ponce City Market, a mixed-use development in a historic warehouse adjacent to the Atlanta BeltLine, is the city’s largest redevelopment project. A walkway connects a new public plaza, the development and the trail, promoting access for both bikes and pedestrians. Jamestown Companies, the project’s developers, observed: “Ponce City Market’s direct connection to the BeltLine is one of the best amenities we have to offer our communities. It is not only an easy way to access the market’s amenities, it also provides our tenants with a great green space that connects them directly to growing neighborhoods.”

Many of the bike amenities at the Ponce City Market are shared by other new, trail-oriented communities. Five hundred spaces allow ample parking for residents and visitors in a secure facility. The development includes retail space and a large central food hall with venders and restaurants, which also makes it a destination on the BeltLine. A free service enables visitors to ride up to the building and leave their bikes with the entrance valet. Hallways and elevators are extra wide to accommodate bikes, so residents can maneuver bikes around the properties. And a bike workroom makes it easy for residents to repair bikes.

In Minneapolis, MoZaic, a mixed-use office building, was developed facing the Midtown Greenway, a 5.5-mile commuter trail that connects to the Uptown Transit Center. To ensure access, the developer, the Ackerberg Group, worked with a nearby development and local officials to construct a bicycle and pedestrian bridge to the Midtown Greenway.

The Flats at Bethesda Avenue in Bethesda, Maryland, a mixed-use development on the site of a former parking lot, is located along an 11-mile Capital Crescent Trail, with runs between Washington, D.C., Bethesda and Silver Spring, Maryland, and is one of the busiest trails in the U.S. with roughly a million users per year. Residents have the option of commuting to work via bike. Additionally, on-site retail establishments attract bicyclists and pedestrians, and the building includes bike parking for the public. An on-site public garage offers a bicycle drop off so commuters can drive to The Flats at Bethesda Avenue, drop off a bike, park in the underground garage and then complete their commute on their bike.

Resorting to Bikes

When Charles Fraser built Sea Pines, bike paths were part of the plan, and it was a bit revolutionary at the time. Today, thanks to a groundswell from residents, those original 15 miles have expended to 112 miles all over Hilton Head, South Carolina. Savvy resort developers understand the value bike amenities and trails can bring, and new resorts often are making walking, hiking and biking as important an amenity as golf.

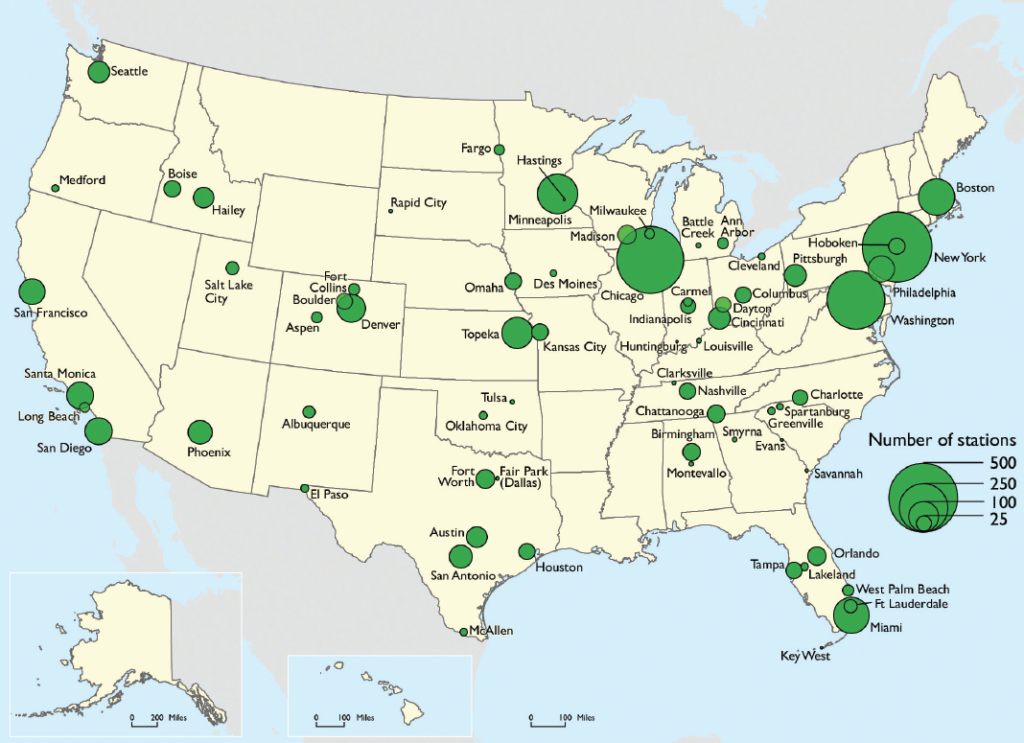

The number of bike-share stations in a given area is depicted here. A total of 46 bike-share systems operate the 2,655 stations in the U.S. For a fee, users can grab a bike at any docking station and then return the bike to another station in the system.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Intermodal Passenger Connectivity Database (as of Feb. 2, 2016)

No Bike, No Problem

Another catalyst for bike infrastructure and trail-oriented development comes from bike-share programs. Anyone who has walked by bike-sharing stations in New York or Washington, D.C., might think this is just another way for tourists to get around the city. But the data and anecdotes tell a different story. Not only are shared bikes a catalyst boosting the number of riders in a city, but they also fill an important gap in the transportation continuum — that last mile between train, subway or parked car to a planned destination. And indications are that bike sharing also pays off with heightened home values. For example, according to ULI, homes in Montreal saw an average increase of $6,123 (U.S.) after the installation of local bike-share stations.

Boulder, Colorado, is not a place where one would expect to see bicycles as an alternative to cars, especially when you take the weather and the terrain into consideration. Yet, Boulder B-cycle, which launched five years ago, is one of the densest bike-sharing programs in the country when measured in terms of stations per capita. “We saw nearly 85,000 trips in 2015, which was close to a 100-percent increase over the previous year’s trips,” says Kevin Bell, marketing and communications director for the program. One-way trips especially have increased, and Bell says people typically use them in concert with commuting, where they will park their car and then use the bikes for quick errands around town during the day. The biggest challenge, Bell says, has been to have people understand that bike share is different than bike ownership.

Leave a Reply