Fundamentally, libraries are simply communal repositories for books, but that utilitarian function is often expressed in architecture that elevates the human spirit.

The first library was built by the Assyrians more than 2,500 years ago in what is now Iraq, and billions of dollars continue to be poured into the construction of extravagant libraries today, despite our full embrace of the Digital Age. Modern libraries not only provide welcoming public gathering places, but their innovative architecture can excite the imagination before even cracking open a book. Kenneth A. Breisch, Ph.D., associate professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Southern California (USC), has authored several books on the evolution of American libraries, including the lushly illustrated American Libraries 1730-1950. He reports that early American libraries were typically private, with no public access to books, and that the Boston Public Library — its flagship is an imposing Renaissance Revival building (1895) — was the first major institution to lend books to the public.

The grandiosity of library buildings conveyed wealth, explains Breisch, who notes, “In Europe, the concept of library design in the Baroque period was to surround gentlemen readers with a luxurious display of books and architecture.” A prime example is Prague’s stunning library hall (circa 1727) at the Klementinum, originally built as part of a Jesuit complex and now occupied by the National Library of the Czech Republic. Ornate ceiling frescoes by German artist Jan Hiebl, giant globes and spiraled mahogany columns with gilded accents contribute to an environment known as the “Baroque Pearl of Prague.” Some believe this venue is the most beautiful Old World library.

Many of the most inspiring structures in Europe are cathedrals, featuring extraordinary expanses of stained glass, and royal palaces with exquisite ornamentation. However, the continent’s historic libraries reveal architectural achievements equal to those created by any archdiocese or monarchy. Acknowledging

religious architecture’s influence on library design, USC’s Professor Breisch suggests, “In some of the grand libraries in Europe, the forms of the cathedral were adapted for the library, with stained glass replaced by walls of books.”

Some families attempt to visit every major league baseball stadium in a single season, others have more intellectual aspirations. In his book, The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders, author Stuart Kells documents his family’s tour of the world’s great libraries. In this loving treatise of history, architecture and human nature, Kells states, “Every library has an atmosphere, even a spirit. Every visit to a library is an encounter with the ethereal phenomena of coherence, beauty and taste.”

Paris has no shortage of magnificent buildings and a notable landmark in the second arrondissement, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s Richelieu site, is dedicated to books. The building’s Salle Ovale, an elliptical reading room with soaring glass ceiling, long wood tables and cushy club chairs, recently reopened after an ambitious, protracted makeover on the occasion of the library’s 300th anniversary. Equally spectacular, with a ceiling that bookworms equate to the Sistine Chapel, is the adjoining Galerie Mazarin in which priceless maps, postage stamps and manuscripts are displayed for the public.

Midtown Manhattan’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, more commonly known as the main branch of the New York Public Library, is a Beaux-Arts landmark conceived in the late 1890s to compete with the palatial libraries in European capitals. The cavernous Rose Main Reading Room features an ornate, muraled ceiling and two long rows of 1,500-pound bronze chandeliers. “This is one of the great libraries of the world and the reading room is a magnificent space that has been beautifully restored, “ says USC’s Kenneth Breisch.

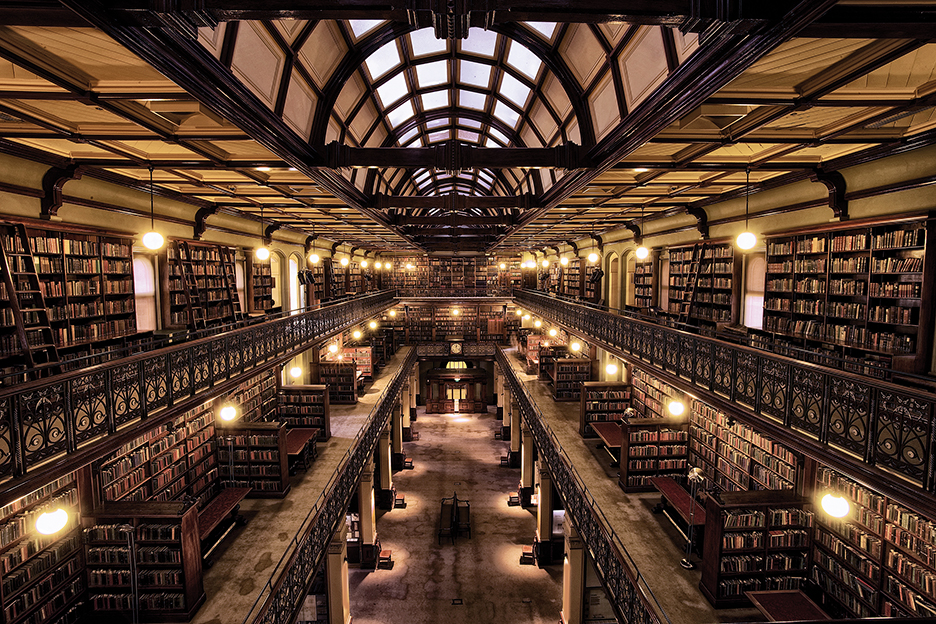

At the State Library of South Australia, in Adelaide, visitors are awed by the interior of the Mortlock Wing, a stunning example of French Renaissance architecture completed in 1884. The long chamber is surrounded by balconies of wrought iron balustrading with gold embellishment, while the glass-capped roof invites natural light. In contrast, a new era of Australian library design is reflected in community facilities in the Sydney suburbs of Bankstown and Surry Hills. Both were designed by fjcstudio, a firm whose sleek libraries across the country have given reading Down Under new sex appeal. “The building became a truly shared place where the whole community could meet and use in different ways,” explained the design team in a narrative on the Surry Hills library for ArchDaily. The architects, headquartered in Sydney, further noted that it was important for the building to reflect the community’s values.

The Piccolomini Library, inside the Gothic cathedral in the Tuscan city of Siena, was built in honor of Pope Pius II. The most memorable features of the library are not priceless collections of books and manuscripts, but remarkable frescoes lining the walls and ceiling, painted by Italian master Pinturicchio and his workshop at the outset of the 16th century. In the center of the room stands a single marble sculpture, a replica of “The Three Graces.”

As the Australian examples demonstrate, not all great libraries are baroque palaces, and some of the most significant are modern structures whose minimalist tendencies are well suited to the functions for which the library is designed. In the 21st century, with virtually every factoid available at the touch of one’s smartphone or tablet, the role of the library has evolved. Public library administrators report that facilities continue to be well attended, but fewer patrons are passing through their doors strictly to find a book.

Today’s public library has a full calendar of readings and seminars, with musicians, scientists and actors presenting their stories in a place where once only silence was tolerated. Seattle’s Central Library, designed by noted Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas of OMA and Seattle-based LMN Architects, opened in 2004. Despite mixed reviews of the monolithic glass-and-steel structure from architecture critics, administrators report that use of the library has far exceeded expectations. LMN Architects partner Sam Miller suggests the library’s unique “book spiral,” a continuous four-story ramp, is a revolutionary way of organizing a multi-floor media collection into a single, continuous loop that retains its organizational structure as the collection grows. USC’s Kenneth Breisch suggests the Seattle facility is an ideal example of a modern library providing full access to virtually the entire collection, a practice its 17th and 18th

century predecessors never anticipated.

“The main floor public space is aptly named the “Living Room” and really functions as such for the city of Seattle,” says Miller. “The library is an extroverted contributor to the life of the city, indoors and out, and welcomes the public into light-filled rooms that astound,” he says. Breisch reports this role of gathering place is another important aspect of the modern library, whose design is more inviting and inclusive than its cloistered antecedents. Oodi, the central library in Helsinki, Finland, is a sleek, sustainable study in glass and wood, with an open-plan reading room on the upper floor nicknamed “Book Heaven.” But this library takes its role as a communal space seriously, incorporating a café, restaurant, movie theater, recording arts studio, and rooms for various creators, whether their medium is a traditional craft or computer-generated 3D printing.

The MVRDV-designed Tianjin Binhai Library in China is among the world’s most futuristic library buildings and its interior is a seductive study in curves somehow squeezed into a more conventional glass exterior. Books are stacked in shelves sleekly integrated into sweeping walls, and a massive, luminescent

globe — it actually serves as a spherical auditorium — is the focal point of a brightly lit atrium.

“We opened the building by creating a beautiful public space inside; a new urban living room is its center,” explains Winy Maas, co-founder of MVRDV, another cutting-edge Dutch firm that designed this library. “The angles and curves are meant to stimulate different uses of the space, such as reading, walking, meeting, and discussing. Together they form the ‘eye’ of the building: to see and be seen,” says Maas.